That is to say, the listener will be incapable of determining whether the sound originated from the back, front, top, bottom or anywhere else along the circumference at the base of a cone at any given distance from the ear. However, no such time or level differences exist for sounds originating along the circumference of circular conical slices, where the cone's axis lies along the line between the two ears.Ĭonsequently, sound waves originating at any point along a given circumference slant height will have ambiguous perceptual coordinates. Most mammals are adept at resolving the location of a sound source using interaural time differences and interaural level differences.

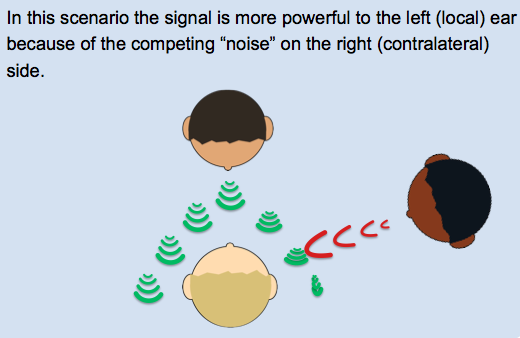

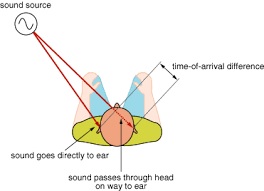

However, there are also many neurons with much more shallow response functions that do not decline to zero spikes. In the auditory midbrain nucleus, the inferior colliculus (IC), many ILD sensitive neurons have response functions that decline steeply from maximum to zero spikes as a function of ILD. Neurons sensitive to interaural level differences (ILDs) are excited by stimulation of one ear and inhibited by stimulation of the other ear, such that the response magnitude of the cell depends on the relative strengths of the two inputs, which in turn, depends on the sound intensities at the ears. Furthermore, a number of recent physiological observations made in the midbrain and brainstem of small mammals have shed considerable doubt on the validity of Jeffress's original ideas. However, because Jeffress's theory is unable to account for the precedence effect, in which only the first of multiple identical sounds is used to determine the sounds' location (thus avoiding confusion caused by echoes), it cannot be entirely used to explain the response. This theory is equivalent to the mathematical procedure of cross-correlation. Some cells are more directly connected to one ear than the other, thus they are specific for a particular interaural time difference. According to Jeffress, this calculation relies on delay lines: neurons in the superior olive which accept innervation from each ear with different connecting axon lengths. In vertebrates, interaural time differences are known to be calculated in the superior olivary nucleus of the brainstem. The sound waves vibrate the tympanic membrane ( ear drum), causing the three bones of the middle ear to vibrate, which then sends the energy through the oval window and into the cochlea where it is changed into a chemical signal by hair cells in the organ of Corti, which synapse onto spiral ganglion fibers that travel through the cochlear nerve into the brain. Through the mechanisms of compression and rarefaction, sound waves travel through the air, bounce off the pinna and concha of the exterior ear, and enter the ear canal. Sound is the perceptual result of mechanical vibrations traveling through a medium such as air or water. Animals with the ability to localize sound have a clear evolutionary advantage. These cues are also used by other animals, such as birds and reptiles, but there may be differences in usage, and there are also localization cues which are absent in the human auditory system, such as the effects of ear movements. The auditory system uses several cues for sound source localization, including time difference and level difference (or intensity difference) between the ears, and spectral information. The sound localization mechanisms of the mammalian auditory system have been extensively studied. Sound localization is a listener's ability to identify the location or origin of a detected sound in direction and distance. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)